#67 Richard Healy, Strategies for Building

2 - 21 June

Richard Healy was born in Hammersmith, London. He graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2008. Healy currently lives and works in London, England.

A conversation between Richard Healy and Samuel Jeffery, 1 June 2010.

Samuel Jeffery: You have spoken about the framing devices in the show as ‘Secondary Structures’ although they play a critical role within the conceptual underpinning of the work. How did these ‘Secondary Structures’ come to play a primary role?

Richard Healy: Yes their role is critical but equally pragmatic. It is interesting that as I have been discussing these objects I have called them ‘secondary structures’ but also ‘support structures’, in any event they have always seemed dissimilar to the drawings or film. All apart from the aluminium structure, which in its making became increasingly rarefied to the extent that it warranted a title. Interestingly I called it ‘Divider’, so how much can a designed object escape it function? I am not sure, in any case the system of support in the show isn’t universal and that really interests me, especially as they are all a single colour. Monochrome was such a modernist obsession with order, so it’s interesting that the yellow supports are, in fact, unequal to one another.

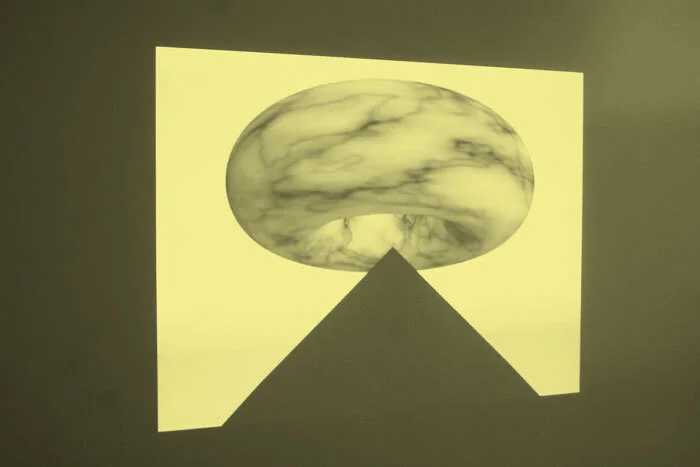

SJ: The works in the show are pregnant with implied practical and design functions. Even the film, which is potentially the most ambiguous of the works, seemingly manages to retain the quality of a prototype, a draft or maybe even something like an architectural mood board. Is it important that all of the artworks maintain a functional implication, that they seem that they could go on to live different lives outside of the gallery?

RH: It is important that they maintain their elements of function, however I always see these functions through the prism of the gallery space in order to highlight and question their value. The idea of them going into the ‘real world’ to follow their functions is obviously implied, however the reality of that occurring seems less appealing to me.

SJ: You have made a decision to place the printouts of the press release and this interview inside the gallery on a purpose made shelf. These are usually placed in the foyer in racks but between us we have decided to change this system. This way the shelf is almost in the real world and seems to be fulfilling a function that we know was once in the ‘real world’. How would you justify that?

RH: Yes it is fulfilling its function, however I would argue that the gallery is not the ‘real world’ but a ‘pseudo-world’. The distinction between the gallery space and the other areas of OUTPOST like the office, foyer and kitchen are apparent. Choosing to place my works, like the shelf, into those spaces would hinder what that object has been made to do. In that situation I would just be making a shelf for OUTPOST. The fabricated, clean space of this gallery offered the opportunity to question its position and the value of its fellow objects, simply because there is less to interrupt these relationships. I would like to point out that gallery can exist in real spaces, galleries can be in peoples living rooms, if that was the case here my approach would have been very different.

SJ: There appear to be worlds illustrated within the drawings and within the film. These are definitely un-real and fabricated worlds but this is a significantly different kind of thing. In what way is it important for these two types of pseudo-space to come together?

RH: I think it is about control, the opportunity to edit a space. The way in which I have been talking about space as real or unreal is problematic I think. What the white-cube gallery offers is control for the artist, less compromise than in the world outside, hence feeling unreal. The drawings and film are a double of this relationship. The way in how I construct space offers meaning to me, where a chair goes in relation to another object etc. Working in OUTPOST has mirrored this mode of using interior space to construct meaning.

SJ: Looking at the work I have become occupied with a notion of time or, more importantly, a lack or uncertainty of a sense of time. Could you talk about that?

RH: There is a definite sense of nostalgia. Visually, the show feels like it could be in the late 1990’s, I like that a lot. There are also references to the late 1960’s with objects I placed in the drawings. However these elements never anchor the work to timescales, like the objects in the film everything is adrift.